N00b's Intro to Async Programming in Cpp

With Folly

Background

Ever since I started working as an engineer, I heard about terms like eventbase, io/cpu threads and futures. I vaguely knew what they were but did not have a clear picture on what was happening under the hood and how they are implemented. Recently, I had a chance to play around with them and wanted to summarize my learning so that I won’t forget. I am sharing it hoping that this will help other n00bs like me. I am not an expert on these subjects so if you find any errors in the info, please let me know!

What is Async programming?

Async I/O lets a thread work on other cpu workload while waiting on I/O instead of blocking on I/O. Let’s say we are building a web server. In the simplest form of multi-threading, where the server creates a new thread to handle each web request, if the request handling involves a lot of I/O (synchronous), many of the threads will be blocked on I/O. As more requests come, the number of threads will keep increasing.

However, having many threads is not ideal. First, not all threads can get executed in parallel. The number of cpu cores determines the true parallelism. If there are more threads than the number of cpu cores, kernel context-switches them in and out to simulate parallel execution. Second, each additional thread comes with memory overhead. Third, increased number of threads will lead to increased number of context-switches. Context-switch itself is not a cheap operation and it also comes with side effects of higher cache misses.

Async programming tries to get the most out each thread by offloading I/O to special purpose pool of threads called I/O thread (Threads that are not I/O thread are called CPU thread). By doing this, it reduces the number of threads and benefits from less memory overhead, context-switch, etc. In this post, I will try to explain the building blocks of cpp async programming and how they interact with each other to achieve async programming.

libevent

In order to reduce the number of total threads, the number I/O threads have to be less than the number of I/Os. This means that a single I/O thread has to handle more than one I/Os. This is where Libevent comes in. Libevent is a construct that enables one I/O thread to handle multiple I/Os at the same time. Each I/O has a file descriptor associated with it. Using Libevent, we can make an event for each file descriptor. An event consists of three things: 1) a file descriptor, 2) interested event for that file descriptor (read, write, or establish a connection), and 3) a callback function. Multiple events can be registered to an eventbase. Once an eventbase goes into a loop, it will block until a timeout or one of the registered events to happen, in which case it will call the callback function for the event.

One I/O thread would have one eventbase associated with it, and just repeat the followings. 1. Waits for an event to happen. 2. Calls the callback function for the event (If multiple events are ready, execute callbacks for all of them) 3. Goes back to #1. The thing to look out for here is that the execution of callback function happens within the same thread that the eventbase is running its event loop. What this means is that, the callback function should finish as quickly as possible in order not to slow down subsequent event handling.

Let’s see some code example with Libevent

- The following code will read input from stdin (fd 0) and print the input to stdout.

#include <event.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <iostream>

void callback(int fd, short event, void* arg) { // (1)

int buf_size = 100;

char buf[buf_size];

int read_size = read(fd, buf, buf_size);

std::cout << buf << std::endl;

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

event_base* eb = event_base_new(); // (2)

event event; // (3)

event_set(&event, STDIN_FILENO, EV_READ | EV_PERSIST, &callback, nullptr); // (3.a)

event_base_set(eb, &event); // (3.b)

event_add(&event, nullptr); // (4)

event_base_loop(eb, 0); // (5)

event_base_free(eb); // (6)

return 0;

}

Let’s go over the code

- This event callback simply reads from the fd and prints to stdout. Event callback signature takes

- file descriptor that triggered the event,

- Event which signifies which event type it is EV_READ, EV_WRITE, EV_TIMEOUT

- Argument passed during event_set. In this callback, I am not doing anything with this, and you can see that I am passing nullptr for this during event_set at (3)

- Creates new event base

- Creates new event and initialize it with appropriate file descriptor (STDIN_FILENO which is 0), event type, callback, and argument (in this case I don’t have any argument I want to pass to the callback so I am passing nullptr).

- Registers the event to the event base. event_base_set() doesn’t register the event to the eventbase. I don’t want any timeout for this event so passing nullptr for timeout.

- Starts eventbase loop. This will loop forever, which means that the code will block at this line. Once the event happens it will execute the callback and block again until the next event. If I want to make it loop just once I can pass in flag like EVLOOP_ONCE, in which case it will block until the first event and execute callback and return.

- Clean up event base, but the code never gets here since it will block at (5).

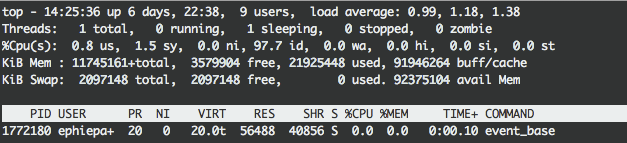

This all happens in one thread top -H -p <PID> would look like this.

But this is boring. Same thing can be done with synchronous read! Let’s take a look at a bit more interesting example.

- This example makes a server that accepts new connections and prints string that clients send to stdout, and it does that all in one thread! Let’s call this a PrintServer.

#include <event.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <iostream>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#define PORT 8080

void callback(int fd, short event, void* arg) { // (1)

int buf_size = 100;

char buf[buf_size];

int read_size = read(fd, buf, buf_size);

buf[read_size] = '\0';

std::cout << "fd: " << fd << " message: " << buf << std::endl;

}

void acceptCallback(int fd, short event, void* arg) { // (2)

event_base* eb = (event_base*)arg;

int new_socket;

struct sockaddr_in address;

int addrlen = sizeof(address);

if ((new_socket =

accept(fd, (struct sockaddr*)&address, (socklen_t*)&addrlen)) < 0) {

perror("accept");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

struct event serverEvent;

event_set(

&serverEvent, new_socket, EV_READ | EV_PERSIST, &callback, nullptr);

event_base_set(eb, &serverEvent);

event_add(&serverEvent, nullptr);

std::cout << "accepted: " << new_socket << std::endl;

}

int setUpServer() { // (3)

// Creates, binds, and listens to a server socket

// Skipped since it doesn't have anything special

return server_fd;

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

event_base* eb = event_base_new();

int serverFd = setUpServer();

event serverEvent;

event_set(&serverEvent, serverFd, EV_READ | EV_PERSIST, &acceptCallback, eb); // (4)

event_base_set(eb, &serverEvent);

event_add(&serverEvent, nullptr);

event_base_loop(eb, 0);

event_base_free(eb);

return 0;

}

Let’s go over the code

- This event callback is exactly the same as the previous example. It just reads from the fd and prints to stdout. This will be called when a client sends input.

- This event callback is called for new connection. This callback will accept the connection to get new fd and create another event with the new fd and callback (1), and register that event to the eventbase which is passed through argument parameter on (4).

- Creating a new server socket and listening to it.

- Registers acceptCallback to server socket and passes eventbase as the argument to the callback function to be used inside (2).

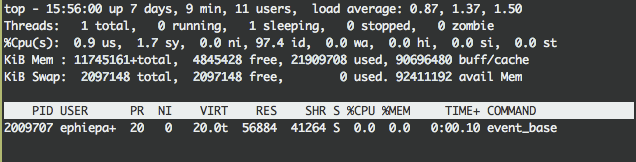

This all happens in one thread as well! top -H -p <PID> would look like this.

If we change callback (1) to the following

void callback(int fd, short event, void* arg) { // (1)

int buf_size = 100;

char buf[buf_size];

int read_size = read(fd, buf, buf_size);

buf[read_size] = '\0';

std::cout << "fd: " << fd << " message: " << buf << std::endl;

for(;;) {} // newly added line

}

This server won’t be able to respond to anything after getting the first input from a client. This is because everything works in a single thread!

Future (folly::Future)

I have talked about eventbase, but in our codebase we rarely work directly with eventbase. We work with future!

Let’s say we have a method that reads a string over the network. In synchronous setting, it will block until the read is finished and return the string to the caller. In asynchronous setting, the method will return immediately before the actual read completes, but what would it return? It would return a future. Future is a handle to the string that want. Through future, we can register callbacks that need to get executed when the read finishes and future gets the real value, and move on to execute other stuff. (Or you can call future::get to wait for the value synchronously)

How does a future get its value? There are two types of future, one is a future that already has a value. You can easily make a future with value by doing folly::makeFuture(value). This is not so interesting. Interesting type of future is one that does not have a value, yet. This type of futures always have a promise associated with it. When the associated promise calls promise::setValue(), the future gets the value and starts executing the registered callback.

When there is a async function that returns a future, it is easy to build things on top of it. But how do we make the fundamental function that does I/O to return a future? I will try to answer the question with the following code examples.

Putting things together

Let’s put things together to make a method that returns a future to a string of user input. But before we get there let’s briefly cover folly::EventBase and folly::EventHandler, which are nice cpp wrapper on libevent. folly::Eventbase is a wrapper around event_base, and folly::EventHandler is a wrapper around an event. (These are some places that folly calls libevent apis 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

- This is a PrintServer implemented with folly.

#include <unistd.h>

#include <iostream>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <folly/io/async/EventBase.h>

#include <folly/io/async/EventHandler.h>

#define PORT 8080

class InputEventHandler : public folly::EventHandler { // (1)

public:

InputEventHandler(folly::EventBase* eventBase, int fd)

: folly::EventHandler(eventBase, fd), fd_(fd) {}

virtual void handlerReady(uint16_t events) noexcept override {

int buf_size = 100;

char buf[buf_size];

int read_size = read(fd_, buf, buf_size);

buf[read_size] = '\0';

std::cout << "fd: " << fd_ << " message: " << buf << std::endl;

}

private:

int fd_;

};

class AcceptEventHandler : public folly::EventHandler { // (2)

public:

AcceptEventHandler(folly::EventBase* eventBase, int fd)

: folly::EventHandler(eventBase, fd), eventBase_(eventBase), fd_(fd) {}

virtual void handlerReady(uint16_t events) noexcept override {

int new_socket;

struct sockaddr_in address;

int addrlen = sizeof(address);

if ((new_socket = accept(

fd_, (struct sockaddr*)&address, (socklen_t*)&addrlen)) < 0) {

perror("accept");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

auto inputEventHandler =

std::make_unique<InputEventHandler>(eventBase_, new_socket);

inputEventHandler->registerHandler(

folly::EventHandler::READ | folly::EventHandler::PERSIST); // (3)

inputEventHandlers_.emplace_back(std::move(inputEventHandler));

}

private:

folly::EventBase* eventBase_;

int fd_;

std::vector<std::unique_ptr<InputEventHandler>> inputEventHandlers_;

};

int setUpServer() {

// same as previous example

// Creates, binds, and listens to a server socket

// Skipped since it doesn't have anything special

return server_fd;

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

folly::EventBase eb; // (4)

int serverFd = setUpServer();

std::cout << serverFd << std::endl;

AcceptEventHandler acceptEventHandler(&eb, serverFd);

acceptEventHandler.registerHandler(

folly::EventHandler::READ | folly::EventHandler::PERSIST); // (5)

eb.loopForever();

return 0;

}

Let’s go over the code

- EventHandler is a wrapper around event. I can create my handler by subclassing EventHandler. It gets fd as a parameter to its constructor, handlerReady is the callback. handlerReady doesn’t need explicit argument parameter since it has access to all of member variables in the handler object. InputEventHandler handles new input from client.

- AcceptEventHandler handles new connection.

- EventHandler needs to be registered to be active

- Creating an eventbase

- EventHandler needs to be registered to be active

Let’s put these together to make an async reader that returns a folly::Future<std::string> whenever there is an input to the fd. In the following example, fd will be 0, stdin.

#include <unistd.h>

#include <iostream>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <folly/futures/Future.h>

#include <folly/io/async/EventBase.h>

#include <folly/io/async/EventHandler.h>

#define PORT 8080

class AsyncReader {

public:

AsyncReader(folly::EventBase* eventBase, int fd)

: inputEventHandler_(this, eventBase, fd),

eventBase_(eventBase),

fd_(fd) {}

folly::SemiFuture<std::string> read() { // (1)

auto contract = folly::makePromiseContract<std::string>(); // (2)

readCallback_ = // (3)

[p = std::move(contract.first)](const std::string& readData) mutable {

p.setValue(readData); // (3.a)

};

inputEventHandler_.registerHandler(folly::EventHandler::READ); // (4)

return std::move(contract.second); // (5)

}

private:

class InputEventHandler : public folly::EventHandler {

public:

InputEventHandler(

AsyncReader* asyncReader,

folly::EventBase* eventBase,

int fd)

: folly::EventHandler(eventBase, fd), asyncReader_(asyncReader) {}

virtual void handlerReady(uint16_t events) noexcept override {

asyncReader_->handleRead();

}

private:

AsyncReader* asyncReader_;

};

void handleRead() {

int buf_size = 100;

char buf[buf_size];

int read_size = ::read(fd_, buf, buf_size);

buf[read_size] = '\0';

readCallback_(std::string(buf)); // (6)

}

folly::Function<void(const std::string&)> readCallback_;

InputEventHandler inputEventHandler_;

folly::EventBase* eventBase_;

int fd_;

};

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

folly::EventBase eb;

AsyncReader asyncReader(&eb, 0);

asyncReader.read().via(&eb).thenValue( // (7)

[](const auto& input) { std::cout << "Yay!: " << input; });

eb.loop();

return 0;

}

Let’s go over the code

- This is the method that will return a future (

folly::SemiFuture) that a client can call. - A future (

folly::SemiFuture) is generated by callfolly::makePromiseContractwhich returns a future and associated promise (std::pair<Promise<T>, SemiFuture<T>>). - Initialize read callback function to be called on read, which will set value to the promise.

- EventHandler needs to be registered to be active

- Return the future to the caller.

- InputEventHandler will call handleRead which will do the actual read and execute the registered callback which will set the promise value.

asyncReader.read()returnsfolly::SemiFuturefor the read data.via(&eb)turns that intofolly::Futurewhich can have a callback. A callback is registered through thenValue method, in this case it will print the message to stdout.via()takes in an executor, which will dictate where the callback would run. In multi-threaded setting with I/O and CPU thread pools,via()can be used to make the callback to be executed in CPU thread.

And that’s it! Thanks for reading! Let me know if you have any question or feedback.

References

While learning about these, I found the following resources to be extremely helpful.